Review Tales

Trusted Reviews and Author Features Since 2016

Interview with ELIZABETH BRUCE

· What’s your favorite thing you have written?

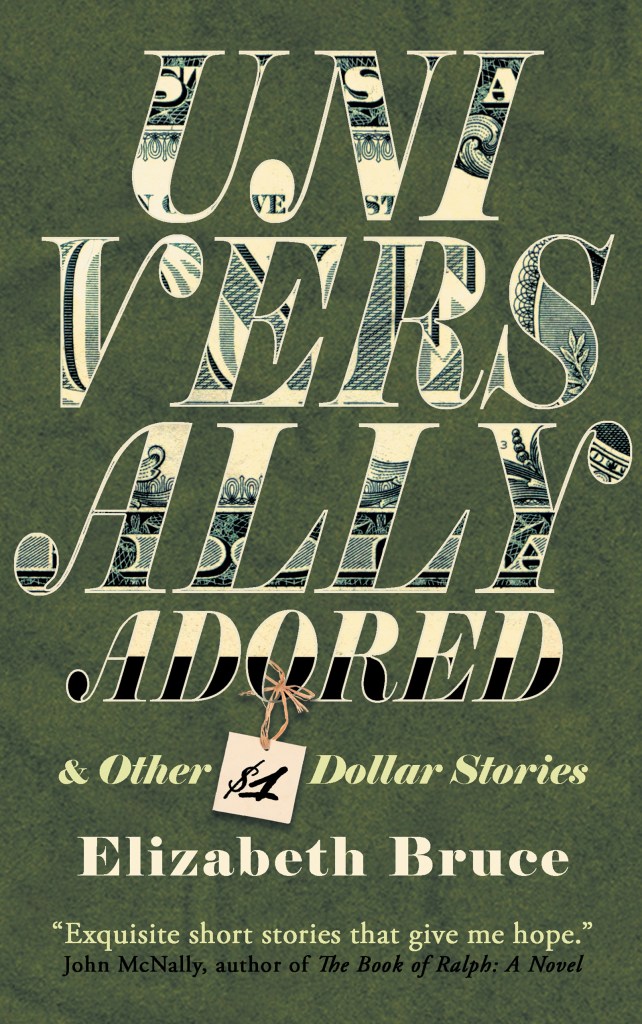

Oh gosh, I love all my characters in everything I’ve written. I really love all the plain-spoken, scrappy characters in my new collection, Universally Adored & Other One Dollar Stories, just published by Vine Leaves Press, in which every story begins with the words “one dollar,” and pivots in some way around the meaning of a dollar.

But I am particularly attached to Thomas Riley, the 81-year-old, World War One protagonist of my debut novel, And Silent Left the Place. Set in April of 1963 in the desert of South Texas, Riley came back from the Great War middle-aged and silent. He can speak, but he doesn’t speak, not to people at least. The mystery of the novel—which takes place in one 24-hour-period—is why Thomas Riley doesn’t speak. The reader does find out, and it’s not what people expect.

I spent a lot of time with Thomas Riley—who is very loosely based on my maternal grandfather, who was a World War One veteran—and his anguish and mythic resolve became very dear to me.

· What’s your favorite thing that someone else has written?

Oh, so many great books. Reading fiction has so deeply enriched my long life. Among the books that still resonate for me are Carson McCullers’ The Ballad of the Sad Café, Jean Toomer’s Cane, The Sybil by Norwegian 1951 Nobel Laureate Pär Lagerkvist, and Cormac McCarthey’s The Road. All about very isolated people who have gone through excruciating situations, and yet they go on.

· What are you working on writing now?

Well, I’ve actually almost finished a rough first draft of a novel-in-progress that’s a sequel of sorts to my collection of one-dollar stories. I take about 10 characters from different dollar stories and plunk them down altogether in the same place. Same characters, same cursory backstories, but a lot more present action and a lot more backstory.

The setting is a fictitious diner in 1980 in the petrochemical town of Texas City, which is right next to my hometown. A lot of these characters have been struggling to keep their heads above water and deal with the challenges of their daily existences. There isn’t a lot of joy in their lives, and a lot of them are pretty lonely. Over the course of the novel, however, various characters find some companionship with each other. I flesh out a lot of really dramatic backstory, history, and personal narratives of some very hard times.

There’s also a deep backstory to the setting which has to do with this terrible industrial accident that happened in 1947—called the Texas City Disaster—which is still the deadliest industrial accident in US history. A French ship full of ammonium nitrate blew up in the Texas City harbor and then a cascade of other explosions happened in the petrochemical refineries, and then the next day another ship full of ammonia nitrate also blew up.

It was a devastating accident. The blast was felt hundreds of miles away. People thought it was an atomic bomb. At least 600 people died, and thousands were injured. Until 9/11, It was also the deadliest loss of firefighter lives in US history. Twenty-seven of the 28 members of the Texas City Volunteer Fire Department were just vaporized. A horrible disaster.

While I don’t have any first-hand experience with it, my folks were living in Galveston at the time. My mother was a nurse, and she was part of the triage team, so I grew up hearing about this.

The Texas City Disaster was also very indicative of the country in 1947. It was the post-war boom, there were almost no environmental controls or occupational health and safety regs. The petroleum industry was flying high, and there wasn’t much of a line in the sand of what industry could or couldn’t do.

This new work is a “polyphonic, discontinuous” novel, meaning that there are multiple POV characters and multiple narrative arcs going on, though they all come together eventually, in part through my very traumatized, somewhat unreliable central narrator who is haunted by the dead. But there’s also a lot of love and newfound joy in the stories; people still find ways to make their lives meaningful.

· Do you have a favorite food or drink that helps you write?

Well, there were times when I could have said red wine, or Irish whiskey, though these days it’s more likely decaf Earl Grey tea with milk.

· What’s your favorite kind of music?

Definitely R&B and the blues. I grew up groovin’ to all the R&B greats—Aretha, Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Marvin Gaye, James Brown, Smokey Robinson, The Supremes, The Temptations, the Righteous Brothers, and Mr. Al Green, and the blues just send me someplace very deep.

· Forest, country, beach, or city?

Hmmm. I grew up just outside of Galveston, but, as a freckled redhead, I really can’t take the sun, but I love the ocean. So. I would say the beach in wintertime or autumn when the crowds are gone, the heat is gone, and the sun is not so strong.

· What movie can you watch over and over again?

Oh gosh, so many great films. Maybe—not to freak your readers out—Apocalypse Now, directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Martin Sheen as Captain Willard, who’s the Marlow character in the Joseph Conrad book, and Marlon Brando as Kurtz. What an extraordinary film, loosely based, as I’m sure your readers know, on Conrad’s turn-of-the-twentieth century novel, Heart of Darkness. I recently re-read Heart of Darknessand was stunned at the candor and accuracy of its portrayal of brutal colonialism.

· What would you like people to know about being an Indie author?

Well, having been published now twice by indie presses—Washington Writers’ Publishing House (WWPH) and Vine Leaves Press (the latter has a cool International Voices of Creative Nonfiction Competition going on until June 1, 2025) and having worked behind the scenes with WWPH, the press that published my debut novel (which will be celebrating 50 years of continuous operation in 2025), I think indie presses are the heart of literary integrity. Maybe they don’t have the money for big advances, and maybe you won’t get reviewed in the New York Times Review of Books, but the dedication and care one experiences with an indie press are priceless. If you want to publish with people who love your book as you love your book, if you want to have creative input and experience real camaraderie with other writers, go with an indie press.

I recently read a long interview between publishing expert Thomas Umstattd Jr. and publishing insider Jane Friedman, that documented how only a tiny sliver of big name authors with the big five publishing houses actually make any money or are robustly promoted by the publisher.

The article talked about something called The Pareto Principle, and how in publishing “The Pareto distribution is like that bell curve chopped in half. A tiny percentage of people make almost all of the money, and everyone else makes almost nothing.”

In fact, interviewer Umstattd summarized it as: “To him who has, more will be given, and to him who does not have, even what he thinks he has will be taken away.”

So, the dream of making it big with a big deal publisher is pretty much an illusion. There are so many amazing small and medium-sized indie presses. I say, go with them.

· When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Oh, growing up in my little Texas town I was one of those kids who dreamed about Paris in the 1920s. You know, The Left Bank, Bohemia, Gertrude Stein and her salons. The setting portrayed a few years earlier in the movie “Moulin Rouge.” All I really wanted to do when I grew up was to get out of my little town and be an artist in a community of artists and “free thinkers.”

For me, intellectual pursuits, creative pursuits, literature, etc., were deeply intertwined with a kind of liberation from conventionality. I considered knowledge to be a path to freedom, part of a long tradition of free thinking that I wanted to be a part of. So, I read and studied and was a good student. I wasn’t valedictorian or anything, and I certainly wasn’t as well behaved as the super Honor Society kids who went on to become doctors or scientists—I spent too much time drinking Wild Turkey Bourbon and smoking Marlboro cigarettes on the Boliver ferry—but I couldn’t wait to go off to college and enmesh myself in an intellectual and artistic world.

Growing up in small town Texas in the 1950s and 60s, you know, the roles for girls and women were so much more restrictive. I used to dream about traveling around the world and sitting in bars in Shanghai or someplace swapping tales with the barkeep. The kind of life the favorite exotic uncle in 19th century novels always had. I didn’t think I could do that as a young woman.

But, in many ways, I have the life I dreamed of. I was a working actor and theatre producer for much of my adulthood until my husband Michael and I had children. I don’t sit in bars anymore, of course, and I never made it to Shanghai. In fact, my world is now incredibly stable—I’ve been married to the same smart guy for almost 40 years; we have two amazing adult children who have partners and families of their own. I’ve never wanted a lot of “stuff” (I still don’t want a lot of stuff; in fact, I’m trying to get rid of all our “stuff”). We’ve lived in the same little rowhouse in NE DC all these years, driven junker cars we bought off our hippie mechanic, lived like graduate students and saved our money, etc.—but my adult life has always been deeply characterized by lifelong learning, teaching, and collaborating with other artists on creative pursuits.

· What does the writing process look like for you?

My writing process has really improved both since I’ve became an empty nester and especially since I retired from my long life as a teaching artist at the bilingual community-based organization, CentroNía.

For the past 25 years, I’ve been a part of in-person and virtual creative writing groups. These have been foundational in keeping me writing, in deepening my narratives and characters, and especially in creating solid structures for the stories. To me, writing groups are the primordial stew of the writing process. They’re where you take your amorphous clusters of literary cells and congeal them into mudfish that can drag themselves onto dry land. I’m part of two in-person prose groups now that I cherish.

In between writing groups, however, nowadays I walk a lot, and sometimes I take my notebook and scribble out a little section of a chapter or dictate my scribbles into my phone. Then I’ll edit it when I get home.

I also have the incredibly good fortune of being married to a man who is a theatre director, a playwright, a scholar, educator, and fellow writer who has what I call “x-ray vision” for structure. Drama is based on narrative arcs, on given circumstances, and subtext, and he has all this training from Aristotle and the Greeks to Shakespeare, Brecht and beyond. Structure is not my strong suit (Plot? What is that?). But Michael can read a piece of writing and tell you exactly where the structure is weak, where the dramatic arc breaks down, etc. It’s a superpower really.

I’ve also been tremendously aided by my collaboration with two virtual writing groups. One is a an online “Poetry Game” that the poet and scholar and close friend Aliki Barnstone, who is a professor at the University of Missouri and former Poet Laureate of Missouri, has online several times a week with other poets. We generate a list of poetic, imagematic words, then everyone clicks off, writes for 45 minutes, then comes back and shares. That’s been enormously valuable in adding depth and texture to rough drafts. I’m also part of an online writing group run by the screenplay writer, solo performer, and facilitator Laura Zam, which is awesome.

· Do you have a blog and what content do you post?

I don’t have a blog, but I do have a podcast, which I co-host with my husband and creative partner, Robert Michael Oliver. It’s called “Creativists in Dialogue: A Podcast Embracing the Creative Life,” and has been supported in part by fellowships from the DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities and HumanitiesDC. We’ve talked with people from all walks of life about the role creativity plays in shaping who they are. We did a deep dive in our “Theatre in Community” series into theatremakers in Washington, DC, from the 1970s to about 2019, and are currently producing another series called “Innovators, Artists & Solutions” about creative problem solvers in a host of fields. It’s free to subscribe at https://Creativists.Substack.com, though of course paid subscriptions are hugely appreciated!

· Where do you get inspiration?

Mostly, I start with characters and place. I don’t tend to write about myself, but I do weave in all kinds of moments that actually happened to me, though I re-cast them with my characters. There are a bunch of real experiences in my collection of one-dollar stories—the Great Mashed Potato War of 1964 and other circumstance, for example, really happened with my best friend Gladys; there are several incidences that really happened with my kids, and a bunch of cultural references from my childhood or youth, like the coin-operated hotel bed massager called “Magic Fingers.”. In my debut novel, And Silent Left the Place, there’s a scene with loose horses that comes from a real experience I had driving through a pass in the Rocky Mountains, and a scene in at the dance hall with this storytelling middle-aged guy who does card tricks that I really experienced in the “Terminal Bar & Grill” outside the Houston bus station in the 70s after I’d been on bus from Guatemala for two days.

The other thing I do is pull a lot from the actor’s toolkit. If an actor has to enter an emotional state in a situation that maybe they haven’t actually experienced, they’ll use “sense memory” to conjure up the relevant emotions. If you’ve never been abandoned in a desert at night, you can instead remember what it felt like to walk through the empty, dark streets of a strange city all by yourself, or being lost somewhere as a child.

· What about writing do you enjoy the most?

Definitely spending time with my characters, getting to know their emotional lives, their life stories, their struggles and triumphs. Like most writers—and absolutely like most actors—I love observing people of all sorts. Where are they, who are they with, what is their posture and body language, how do they walk, what are they wearing, what’s going on, what can you glean from their external presentation of self? It is endlessly fascinating and so deeply human.

I once walked through the mean streets of DC, back in the 1980s, with a streetwise fellow who did political work for this local politician, back when I was doing outreach for our theatre that had just opened in his neighborhood. He could scan the street and tell you exactly what everyone’s hustle was. Who was the top dog, who was a newbie, etc. In the middle of the day, we went into this bar named “Chuck’s” that was on the 1400 block of Irving Street, NW, way before the neighborhood of Columbia Heights was all re-developed. It was a Black, drag bar; the owner, Chuck, had this incredible personal story, and the people in the bar were so far outside of what I experienced in my daily life. The bar is long since gone, but I was always grateful to this fellow for sharing his ability to size up a landscape instantly.

I try to telegraph some of that to my readers by creating “a stage on the page,” where you can tell a lot about a character by their placement in a place, their posture, gestures, etc., the same way a stage play or a film does.

· What is the most challenging part of writing for you?

Oh, rewriting. Fixing what doesn’t work. Ga-a-a, it is so hard. As I said, structure is not my forte; I tend to write episodically, with a lot of associative tangents and backstory. I’m more focused on voice and texture than plot. I can get really attached to some riff of dialogue or memory. So, I usually have to step back and rearrange things, or cut things out. “Kill your darlings” as the saying goes, which has been attributed to everyone from Faulkner to Welty, Chekhov to Oscar Wilde to Stephen King. Google tells me, however, that it actually comes from a 1914 British lecturer named Arthur Quiller-Couch (who knew?).

· How have you grown as a writer?

I’ve learned so much in the past three decades. Writing fiction, poetry, any writing, is a skill, like bricklaying or stone carving or cooking, There are tons of techniques for a writer to learn and try to master. How do you establish place and setting? What is point of view and how do you maintain it? How do you move forward or backward in time? How do you weave in backstory? And on and on. There are two craft books I totally recommend. One is Vivid and Continuous by John McNally and the other is Elements of the Writing Craft by Robert Olmstead. They’re both incredible writers. Olmstead says he should charge $1,000 for that book because it contains everything he knows about writing.

While I don’t have an MFA, I have a lot of continuing education as a creative writer. I was incredibly fortunate to participate in the inaugural Heritage Writers Workshop at George Mason University with the great Richard Bausch, who was so incredibly encouraging (a project that he continues at Chapman University). I was also so fortunate to participate in the Jenny McKean Moore Workshop at George Washington University with the amazing writer John McNally

I also went to some writing conferences and retreats, including the Rappahannock Fiction Writers Retreat where I got to study with the late, great Lee K. Abbott and the amazing writer Janet Peery. I also took a fiction writing class twice at Georgetown University’s Continuing Ed with the awesome writer Liam Callanan. I remain so indebted to all of them.

Thank you so much for giving me this opportunity to share about my writing and my books. This has been so much fun!

Your readers can find out about more about my new collection, Universally Adored and Other One Dollar Stories here or about my debut novel, And Silent Left the Place, here. Or learn more about me or my other work at https://elizabethbrucedc.com.

About the Author:

Elizabeth Bruce’s debut story collection, Universally Adored & Other One Dollar Stories, is forthcoming in January 2024 from the Athens, Greece-based Vine Leaves Press. Her debut novel, And Silent Left the Place, won Washington Writers’ Publishing House’s Fiction Award, ForeWord Magazine’s Bronze Fiction Prize, and was one of two finalists for the Texas Institute of Letters’ Steven Turner Award for Best Work of First Fiction. Bruce has published prose in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Sweden, Romania, India, South Korea, Malawi, Yemen, and The Philippines, including in FireWords Quarterly, Pure Slush, takahē magazine, The Ilanot Review,Spadina Literary Review, Inklette, Lines & Stars, and others, as well as in such anthologies from Paycock Press’ Gargoyle series, Weasel Press’ How Well You Walk through Madness: An Anthology of Beat, Vine Leaves Literary Journal: A Collection of Vignettes from Across the Globe; Madville Publishing’s Muddy Backroads, Two Thirds North, multiple Gargoyle anthologies, and Washington Writers’ Publishing House’s This Is What America Looks Like. Follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Discover more from Review Tales

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Universally Adored and Other One Dollar Stories by Elizabeth Bruce (March 2024) |

Thank you for hosting Elizabeth today!

LikeLike